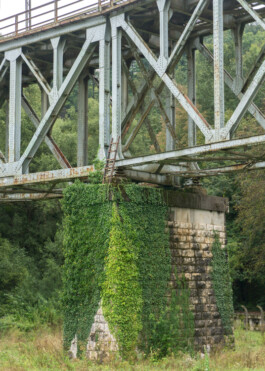

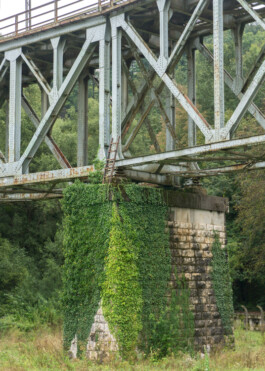

Status Quo Ladder Halle, GER, 2022

On a narrow ledge above the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, an inconspicuous wooden ladder leans against the wall. The oldest evidence of its existence is a woodcut from 1728 on which the ladder is depicted. But it may also have been there for much longer. No one knows for sure. The original function of the ladder is also not entirely clear: was it left there after work on one of the windows was done? Was it once used to enter the church when the gates were closed?

Only one thing is clear: the ladder must not be removed because it is part of the so-called Status Quo. This principle regulates which parts of the church belong to which of the six Christian confessions which share this perhaps holiest place in Christianity: Catholics, Copts, Greek, Syrian, and Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, and Armenian Apostolics. One can imagine the Status Quo like a complicated cleaning schedule in a sizeable flat-sharing community: it regulates who owns which shrines, which tasks are to be done by whom, and who is allowed to pray where at what times. As in every sizeable flat-sharing community, this principle leads to disputes - and these have a long tradition. Between the monks who look after and care for the church, it sometimes comes to physical violence.

The centuries-old dispute between the confessions means that everything at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre remains as it is. Because to change something, everyone would have to agree. Every building measure, every change without the agreement of all those involved, would be a violation of the Status Quo - including the utterly useless ladder. So it has become what it embodies today: an integral part of the architecture of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a funny anecdote in historical city tours, a symbol of the absurdity of religious conflicts.

Mathias Weinfurter learned about this ladder during a stay in Jerusalem in 2013. Based on this, he began to install his Status Quo Ladders in various places in 2018.

Text by Nils Altland

Status Quo Ladder Bergamo, ITA, 2021

Status Quo Ladder Jeju, KOR, 2019

Status Quo Ladder Tel Aviv, ISR, 2018

Status Quo Ladder Belgrade, SRB, 2024

Status Quo Ladder Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

Status Quo Ladder Kharkiv, UKR, 2018

Status Quo Ladder Bogota, COL, 2019

Status Quo Ladder Kulen Vakuf, BIH, 2018

Status Quo Ladder Berlin, GER, 2021

Credits:

Places: Jerusalem, Kharkiv, Kulen Vakuf, Tel Aviv, Offenbach, Cologne, Bogota, Ambalema, Giessen, Müllrose, Trondheim, Jeju, Bergamo, Siegburg, Berlin, Kobarid, Martin Brod, Haßleben, Wiesbaden, Halle, Gvozd, Krugersdorp, Sankt Augustin, Belgrade // acknowledgement: Ado, Nils Altland, Clemens Behr, Anna Boldt, Max Brück, Katie Gaj, Sophia Igel, Rachel Herter, Martin Kähler, Lea Kulens, Juliane Kutter, Malte Möller, Jan Paul Müller, Deborah Nerlich, Lisa Nürnberger, Joëlle Pidoux, Eric Reh, Linda Weiß, Zinitschka

Status Quo Ladder Halle, GER, 2022

On a narrow ledge above the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, an inconspicuous wooden ladder leans against the wall. The oldest evidence of its existence is a woodcut from 1728 on which the ladder is depicted. But it may also have been there for much longer. No one knows for sure. The original function of the ladder is also not entirely clear: was it left there after work on one of the windows was done? Was it once used to enter the church when the gates were closed?

Only one thing is clear: the ladder must not be removed because it is part of the so-called Status Quo. This principle regulates which parts of the church belong to which of the six Christian confessions which share this perhaps holiest place in Christianity: Catholics, Copts, Greek, Syrian, and Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, and Armenian Apostolics. One can imagine the Status Quo like a complicated cleaning schedule in a sizeable flat-sharing community: it regulates who owns which shrines, which tasks are to be done by whom, and who is allowed to pray where at what times. As in every sizeable flat-sharing community, this principle leads to disputes - and these have a long tradition. Between the monks who look after and care for the church, it sometimes comes to physical violence.

The centuries-old dispute between the confessions means that everything at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre remains as it is. Because to change something, everyone would have to agree. Every building measure, every change without the agreement of all those involved, would be a violation of the Status Quo - including the utterly useless ladder. So it has become what it embodies today: an integral part of the architecture of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a funny anecdote in historical city tours, a symbol of the absurdity of religious conflicts.

Mathias Weinfurter learned about this ladder during a stay in Jerusalem in 2013. Based on this, he began to install his Status Quo Ladders in various places in 2018.

Text by Nils Altland

Status Quo Ladder Bergamo, ITA, 2021

Status Quo Ladder Jeju, KOR, 2019

Status Quo Ladder Tel Aviv, ISR, 2018

Status Quo Ladder Belgrade, SRB, 2024

Status Quo Ladder Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

Status Quo Ladder Kharkiv, UKR, 2018

Status Quo Ladder Bogota, COL, 2019

Status Quo Ladder Berlin, GER, 2021

Status Quo Ladder Kulen Vakuf, BIH, 2018

Credits:

Places: Jerusalem, Kharkiv, Kulen Vakuf, Tel Aviv, Offenbach, Cologne, Bogota, Ambalema, Giessen, Müllrose, Trondheim, Jeju, Bergamo, Siegburg, Berlin, Kobarid, Martin Brod, Haßleben, Wiesbaden, Halle, Gvozd, Krugersdorp, Sankt Augustin, Belgrade // acknowledgement: Ado, Nils Altland, Clemens Behr, Anna Boldt, Max Brück, Katie Gaj, Sophia Igel, Rachel Herter, Martin Kähler, Lea Kulens, Juliane Kutter, Malte Möller, Jan Paul Müller, Deborah Nerlich, Lisa Nürnberger, Joëlle Pidoux, Eric Reh, Linda Weiß, Zinitschka