EN | DE

A Colombian portrait with blurs

Peter Stohler, Yvan Sikiaridis, 2020

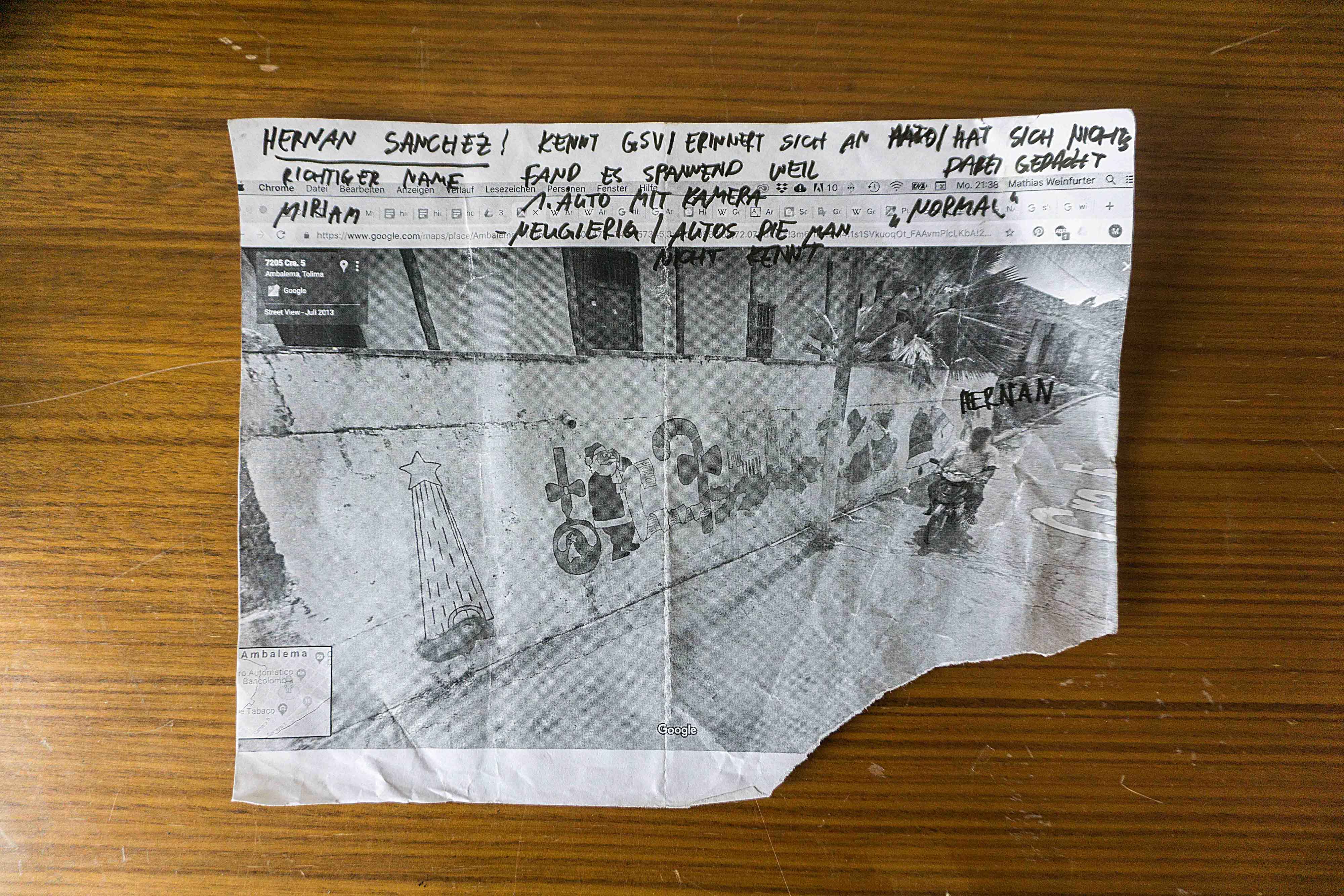

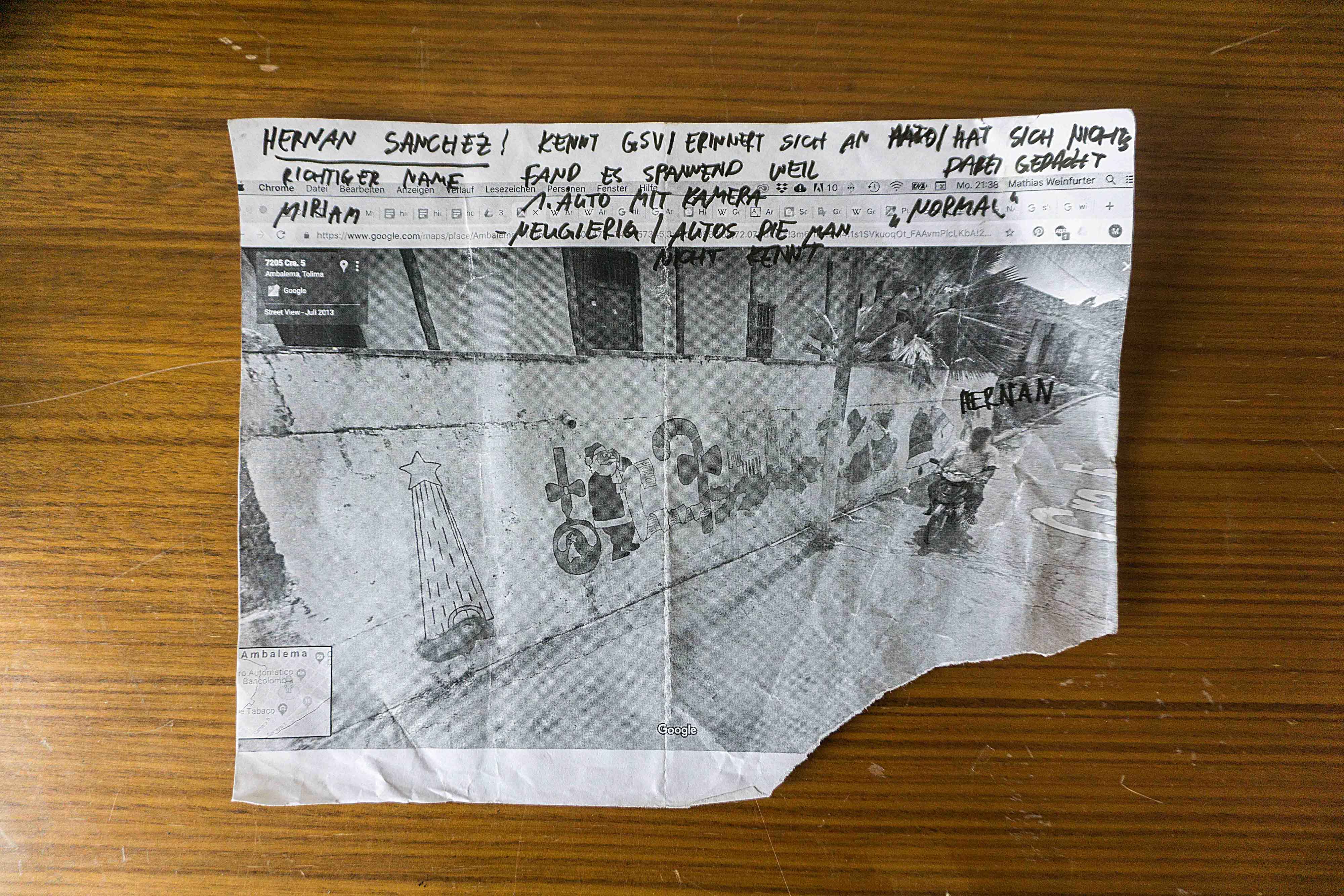

Ambalema is a sleepy little town on the Rio Magdalena, about two and a half hours by car east of the Colombian capital Bogotá. When looking for it on Google Maps, one sees a pattern of roads marked blue that can each be explored with Street View. In July 2013, a special vehicle of the Google corporation drove through Ambalema with an almost three-meter-high rack on top equipped with dome cameras taking photos. For reasons of data protection, a filter blurred all faces. The Latin America expert Anna Boldt (*1993) and Mathias Weinfurter (*1989), who studied at the University of Art and Design in Offenbach, used these Street View images as the starting point of Miradas Borrosas (2019).

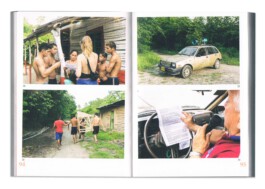

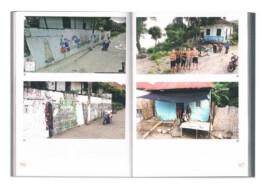

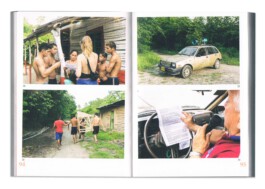

With Google Street View prints, the artist duo Boldt and Weinfurter set off to meet the people who were accidentally captured by the cameras at the time. Even if their faces cannot be clearly recognized—as opposed to how it would be in anonymous big cities—they were able to meet them. For in the six years between the arrival of the Google vehicle and their film project, not much had changed in the small provincial town. To get into conversation with the people, they built a tower, lovingly called “Torre Paris,” with which they walked through town assisted by youths. The tower is as high as the Google camera was, and from there they filmed the residents gazing at the camera. Their faces were again blurred, this time by the artist duo. In the exhibition space, the tower is presented near the video projection.

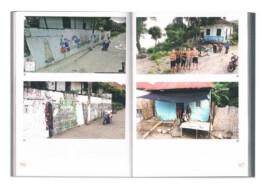

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

At the centre of the nine-minute video is the narrator Alfredo Martínez a grey-haired man of around 60, a talented storyteller known throughout Ambalema. He doesn't tell stories on the village square or around a campfire, but drives his car through town announcing the local news through two megaphones on the roof. For Martínez, the artist duo wrote a story about that day in July in Spanish, which he reads quite vividly from a sheet of paper. People are introduced who observed the events at the time—for example Hugo, whom one sees on a blue motor scooter, or Don Pedro, a fisherman posing in shorts in front of his small house. Their faces are also blurred.

As a viewer, one enjoys engaging with this charming story, especially because of the talented storyteller. Even if the blurred faces establish a distance that needs getting used to, one senses the artist duo’s interest in the local residents. As Mathias Weinfurter says: “Sometimes it’s enough to write a bit of a life story together and gain trust and overcome biases through an open exchange.” Will we get to know these people even better in one of their next projects?

Anna Boldt and Mathias Weinfurter in conversation with Ivan Sikiaridis

Video still of Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

Ivan Sikiaridis: Why does your work bear the title Miradas Borrosas (Eng. Blurred Views)?

Mathias Weinfurter: The project is based on images that Google creates in many places throughout the world with Google Street View. Google is criticised a lot, also with regard to the private sphere and personality rights of the depicted people. The company ended this criticism and developed an algorithm that blurs the faces of persons in the images.

Protection through the algorithm presumably works in a city like Bogotá, where there is generally greater anonymity and people constantly move about in their daily lives. In Colombian villages such as Ambalema, however, temporality and the adherence to places stand in a different relationship. A person can be associated with a location more easily there.

The Google photos of Ambalema were made in 2013, and a person who stood in front of their store at the time probably still stands there every day in 2020. For this reason, it is of relatively little use when the faces in Ambalema are blurred to protect people, because they can always be associated with a place and also a style.

For the project, we used prints of the Google images which we showed around in the village. But despite the blurred faces, one clearly notices in the pictures from Ambalema that many people stopped and looked into the camera.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

IS: How did you develop the project in narrative terms?

Anna Boldt: When developing the short story, it was important for us to stick as close as possible to what the people said and especially to relate their wording. The decision to mix real and fictive elements made it possible to portray individual characters, but elsewhere also to highlight just individual sentences or terms that recurred in the village. This allowed us to put together a story out of numerous fragments.

For our collaboration with Alfredo Martínez, who ultimately performed the text, it was necessary that the wording remained familiar and realistic so that his voice could convey it as appropriately as possible. The audio level of the work is supported by the voice of Alfredo Martínez. It played a big role that it was his voice, because it could be heard through the megaphones on the roof of his car and was familiar to the residents. Everyone knows him well, since he drives his car through the village and announces the news.

It was very important that he was willing to drive through Ambalema for a day and recite our short story for the performance, because it allowed us to establish this directness on site and later have the audience experience the spatial installation via the audio track of the film.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

MW: For the visual part, we restaged the Google images with the residents. To this end, we had to make contact with them. It was sensible not just to walk through the village with the camera like tourists but to bring something spectacular along. We therefore used a sculptural setup as a possibility to start a conversation. Of course, many people addressed us directly.

For the tower we built, we used material that we could find and work with on location. It was important that it could be moved around in the village and especially that it was freely accessible. It was nice when one resident called the tower “Torre Paris” and said that it was Ambalema’s Eiffel Tower. The Torre Paris offered the perfect opportunity to enter into a conversation.

AB: We built it with the intention of imitating the height of the camera on the Google vehicle. The scenes in our short film were shot from this tower, from a height of 2.80 metres. The interpretation or restaging of the actual Google photos shows the steep perspective from above, as it can be found on the internet.

IS: How was your intervention received by the people in Ambalema?

MW: Many people were really keen on taking part in the project. Our appearance, the detective game with the printed photos, the tower and the performance with Alfredo Martínez attracted attention, and many people were curious and kept on asking us what we were doing and how they could participate. But sometimes it’s enough to write a bit of a life story together and gain trust and overcome biases through an open exchange.

The conversation was held on 20 May 2020 via videoconference.

Published in Storytelling, Peter Stohler, Yvan Sikiaridis (Ed.), published by modo Verlag & GRIMMWELT Kassel, ISBN 978-3-86833-293-3, 2020

EN | DE

A Colombian portrait with blurs

Peter Stohler, Yvan Sikiaridis, 2020

Ambalema is a sleepy little town on the Rio Magdalena, about two and a half hours by car east of the Colombian capital Bogotá. When looking for it on Google Maps, one sees a pattern of roads marked blue that can each be explored with Street View. In July 2013, a special vehicle of the Google corporation drove through Ambalema with an almost three-meter-high rack on top equipped with dome cameras taking photos. For reasons of data protection, a filter blurred all faces. The Latin America expert Anna Boldt (*1993) and Mathias Weinfurter (*1989), who studied at the University of Art and Design in Offenbach, used these Street View images as the starting point of Miradas Borrosas (2019).

With Google Street View prints, the artist duo Boldt and Weinfurter set off to meet the people who were accidentally captured by the cameras at the time. Even if their faces cannot be clearly recognized—as opposed to how it would be in anonymous big cities—they were able to meet them. For in the six years between the arrival of the Google vehicle and their film project, not much had changed in the small provincial town. To get into conversation with the people, they built a tower, lovingly called “Torre Paris,” with which they walked through town assisted by youths. The tower is as high as the Google camera was, and from there they filmed the residents gazing at the camera. Their faces were again blurred, this time by the artist duo. In the exhibition space, the tower is presented near the video projection.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

At the centre of the nine-minute video is the narrator Alfredo Martínez a grey-haired man of around 60, a talented storyteller known throughout Ambalema. He doesn't tell stories on the village square or around a campfire, but drives his car through town announcing the local news through two megaphones on the roof. For Martínez, the artist duo wrote a story about that day in July in Spanish, which he reads quite vividly from a sheet of paper. People are introduced who observed the events at the time—for example Hugo, whom one sees on a blue motor scooter, or Don Pedro, a fisherman posing in shorts in front of his small house. Their faces are also blurred.

As a viewer, one enjoys engaging with this charming story, especially because of the talented storyteller. Even if the blurred faces establish a distance that needs getting used to, one senses the artist duo’s interest in the local residents. As Mathias Weinfurter says: “Sometimes it’s enough to write a bit of a life story together and gain trust and overcome biases through an open exchange.” Will we get to know these people even better in one of their next projects?

Anna Boldt and Mathias Weinfurter in conversation with Ivan Sikiaridis

Video still of Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

Ivan Sikiaridis: Why does your work bear the title Miradas Borrosas (Eng. Blurred Views)?

Mathias Weinfurter: The project is based on images that Google creates in many places throughout the world with Google Street View. Google is criticised a lot, also with regard to the private sphere and personality rights of the depicted people. The company ended this criticism and developed an algorithm that blurs the faces of persons in the images.

Protection through the algorithm presumably works in a city like Bogotá, where there is generally greater anonymity and people constantly move about in their daily lives. In Colombian villages such as Ambalema, however, temporality and the adherence to places stand in a different relationship. A person can be associated with a location more easily there.

The Google photos of Ambalema were made in 2013, and a person who stood in front of their store at the time probably still stands there every day in 2020. For this reason, it is of relatively little use when the faces in Ambalema are blurred to protect people, because they can always be associated with a place and also a style.

For the project, we used prints of the Google images which we showed around in the village. But despite the blurred faces, one clearly notices in the pictures from Ambalema that many people stopped and looked into the camera.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

IS: How did you develop the project in narrative terms?

Anna Boldt: When developing the short story, it was important for us to stick as close as possible to what the people said and especially to relate their wording. The decision to mix real and fictive elements made it possible to portray individual characters, but elsewhere also to highlight just individual sentences or terms that recurred in the village. This allowed us to put together a story out of numerous fragments.

For our collaboration with Alfredo Martínez, who ultimately performed the text, it was necessary that the wording remained familiar and realistic so that his voice could convey it as appropriately as possible. The audio level of the work is supported by the voice of Alfredo Martínez. It played a big role that it was his voice, because it could be heard through the megaphones on the roof of his car and was familiar to the residents. Everyone knows him well, since he drives his car through the village and announces the news.

It was very important that he was willing to drive through Ambalema for a day and recite our short story for the performance, because it allowed us to establish this directness on site and later have the audience experience the spatial installation via the audio track of the film.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

MW: For the visual part, we restaged the Google images with the residents. To this end, we had to make contact with them. It was sensible not just to walk through the village with the camera like tourists but to bring something spectacular along. We therefore used a sculptural setup as a possibility to start a conversation. Of course, many people addressed us directly.

For the tower we built, we used material that we could find and work with on location. It was important that it could be moved around in the village and especially that it was freely accessible. It was nice when one resident called the tower “Torre Paris” and said that it was Ambalema’s Eiffel Tower. The Torre Paris offered the perfect opportunity to enter into a conversation.

AB: We built it with the intention of imitating the height of the camera on the Google vehicle. The scenes in our short film were shot from this tower, from a height of 2.80 metres. The interpretation or restaging of the actual Google photos shows the steep perspective from above, as it can be found on the internet.

IS: How was your intervention received by the people in Ambalema?

MW: Many people were really keen on taking part in the project. Our appearance, the detective game with the printed photos, the tower and the performance with Alfredo Martínez attracted attention, and many people were curious and kept on asking us what we were doing and how they could participate. But sometimes it’s enough to write a bit of a life story together and gain trust and overcome biases through an open exchange.

The conversation was held on 20 May 2020 via videoconference.

Published in Storytelling, Peter Stohler, Yvan Sikiaridis (Ed.), published by modo Verlag & GRIMMWELT Kassel, ISBN 978-3-86833-293-3, 2020