Owners, Guests, and Trespassers

Sven Christian in conversation with Jeremy Wafer, Anna Boldt, and Mathias Weinfurter, 2023

On Thursday, 15 December, the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture and NIROX hosted a webinar with Jeremy Wafer, Anna Boldt, and Mathias Weinfurter, moderated by Sven Christian. The webinar took place in the early stages of Boldt and Weinfurter’s residency at NIROX, and served as an introduction to Wafer’s work, who took up residence a few months later, on 16 May 2023, in preperation for an exhibition at Goodman Gallery that opens on 9 July 2023.

The webinar focused on land, mapping, surveillance, and the potential failures of photographic representation. It included the screening of a short film by Boldt and Weinfurter, titled Miradas Borrosas (Blurry Gazes), which revolves around the presence of Google Street View (GSV) in the small Colombian village of Ambalema, before delving into their current research on GSV in Nietgedacht, 40km from Johannesburg, as well as Wafer’s own photographic, sculptural, and sitespecific interventions, such as Ashburton (1977), Fence (1979), and Xoe (2000).

The conversation was subsequently transcribed by Zanele Mashinini and included here to provide some background information about the works produced during their respective residencies.

Installation view of Palisade Fences at NIROX Sculpture Park, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

Sven Christian: Jeremy, let’s start by talking about the show that you’re preparing for, at Goodman Gallery?

Jeremy Wafer: The show is a continuation of works that I’ve been doing. I did a small show at Goodman Gallery in London in February / March that included older works — that curvy wax piece and some smaller ones that combine mapping and marking. There was a little stripey work, and I’m currently working on a whole series of drawings, taking pages from a financial newspaper andgoing through a series of permutations of single and broken lines. There will be about sixty of these drawings. It’s the sort of thing that I can do while I’m here in Paris. I have a room studio, so I can’t really make the sculptural works here. At the moment it’s quite a rhythmical exercise. Then I’m expecting to work on a series of maps. I’ve got a series of 1:50,000 maps arriving from Johannesburg, with all sorts of South African locations. I really love their quality, as physical objects. It’s interesting to go to different countries and look for the standard government maps. They have a very different physical format. The South African ones are particularly nice. They‘re printed on strong paper, in portrait format, and are beautifully produced. I have access to a pile of those, and I’m going to interfere with the map — blocking out areas, treating them as signs or fields. . . Sometimes painting out the actual map, leaving out all the descriptive stuff around the edge. That’s one set of work, but I’m also anticipating about eight sculptural pieces of different sizes.

I’m getting to a stage where I just want to work on a fairly simple, direct idea. I suppose the running thread through a lot of the work is an interest in the materiality of ordinary stuff — tar, soap, stuff like that, which is quite low budget. In recent years my exhibitions have included a mixture of things that are not directly connected, but when there are a whole lot of works together, say six or seven, they establish an open kind of relationship.

SC: The ones from the Financial Times look like they’re redacted.

JW: Because it’s newspaper, I suppose those marks take on that quality, particularly in light of South African history. It’s not something I want to make too much of, but a lot of these works also resonate with personal experience. A long time ago, when I was in the army, I was a clerk, and had to block out things that were in soldiers’ letters; I had to read the letters and take a black pen and remove anything that might relate to a mission: like if a soldier wrote and said, ‘Oh, we were at X, Y, or Z in Namibia.’ You weren’t allowed to say that. There was this thing about location and blocking, but I don’t think these works stem from that. When you work with things, you start to see connections to a host of other experiences or to things that you have done or have had some relationship to.

Video still of Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

SC: Reading those letters must have been a strangely intimate experience. There’s this inadvertent voyeuristic element that overlaps with the research that Mathias and Anna are doing on Google Street View [GSV], which began in Colombia. Perhaps you could give some background context to it, your research, and the project that came about as a result?

Mathias Weinfurter: Sure. Miradas Borrosas was realised by Anna and I during a residency in February 2019 in the small village of Ambalema, five hours west of Bogota. To prepare, we wanted to get a better sense of the village, so we went onto GSV, where we were able to ‘walk’ through, while sitting in Germany. The GSV content for this village was produced in July 2013, so at the time of our project it was already six years old. The images captured a number of people standing outside their homes, in front of shops, in the park. . . You saw a lot of people, with their faces blurred. Some look straight into the camera.

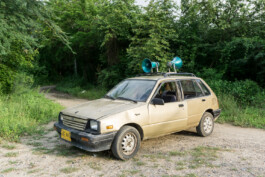

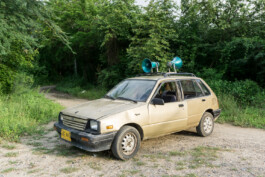

Anna Boldt: When we arrived there, we noticed that very little had changed. The streets and buildings look almost the same. A lot of the same people featured on GSV were also often in the same place. We began to converse with them, and found that they didn’t know about GSV; that they don’t use this service. We had brought printouts of the images with us, and they were surprised by them. It turns out that, in a place like Ambalema, which is really small, it was easy to find these people because everyone knows each other. Although their faces were blurred, they were still recognisable. We wanted to know if they could remember the day when these pictures were taken, and it was fascinating to hear their stories. There was a lot of speculation about the car, in particular, because it’s a very weird looking car with this camera on top. In the context of Colombia, many people thought it was related to the drug war; these paramilitary groups that were entering such villages at the time, or that this vehicle was somehow connected to the police.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

MW: We were so inspired by these conversations about the day that the car passed through the village that we wrote a story, which you hear in the film. We then collaborated with Alfredo Martínez, who has this megaphone equipped to his car. It’s quite commonplace in these small Colombian villages. Everyday Alfredo drives around, speaking into the megaphone, to tell the news. You can pay him to spread news about, say, the opening of a new restaurant. So together with him we realised a performance, in which he drove around reading the story that we wrote about the day when GSV passed through Ambalema. In the story, we tried to include a number of the speculations that we’d heard.

Our second intervention was trying to reinterpret the images from GSV, in cooperation with the inhabitants. We built a wooden tower that echoed the perspective of that on the GSV car. We went through the town with this tower, trying to recapture images of the same places, from the same perspective. A lot of the time we found the same protagonists there, as before. The documentation of both interventions is reflected in the film.

Of course, we also did further research, and found some historical references that were quite inspiring. The first was a film, The man with a movie camera, that was produced by Dziga Vertov in 1929, in Ukraine. A lot of the scenes are filmed from a car with a camera on top. The film is about him going around filming himself, so there’s footage from the car but also of him doing this intervention. Then we found an interesting example from the 60s, of Josep Planas i Montanyà. He was a photographer, living and working on the isle of Mallorca. He ran a business producing postcards, and would go around in his car, which also had a camera on top, to document the streets and island.

GSV was launched, almost worldwide, in 2008. It led to some artistic projects, such as Vince Staples’ music video, FUN! (2018), by director Calmatic. The video combines the aesthetics and mechanisms of GSV with the codes of hip-hop and pop culture.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

SC: That video begins with a distant view of the Earth, then zooms into a particular community, a particular suburb, and the different inhabitants going about their day. There’s a voyeuristic element to it, but what struck me is how the director flips this — it becomes a way of putting one’s community on the map and reflects a kind of agency or reclaiming of that digital space. Jeremy, I know that as a student you also started documenting the various houses in the street in which you lived. . .

JW: Ja. I suppose I came to photography as a very direct form of documentation. It was systematic for me, like mapping. My early student work was just photographing all the houses in my street. I would start at one end and go all the way down. When you start doing that, you’re not making any aesthetic choices. You have a system in place which you work through. In the process, one has other sorts of interactions. People came out of their homes to ask if I was an estate agent. That sort of thing wasn’t part of the work, but I suppose it’s one of the reasons why I was interested in your film, because you see the relationship between the systematic, objective component of GSV, going up an down the street, but you also layer that with a more personal, human narrative. It’s a poetic and imaginative kind of layering.

I began thinking about mapping space before GSV or Google Earth existed; accessing aerial photographs of sites which I myself would not go to. In the context of South Africa, which is such a demarcated country, the separation and division that one experiences is not only of people but of space. There were places that one could or could not visit, and I became interested in how such images might provide a form of access, through this dislocated eye — how you could see something without physically going there. There’s this imaginative transfer. For example, there is an aerial photograph of an area near where I grew up. During apartheid it was demarcated as a ‘native reserve’; an area for black people. Now, I could see this area from the veranda of my parents’ farm, in the white area. We could look up into the hills and see it, but we never went there. It was a place which wasn’t ‘for us’; a place which was ‘other.’ My only access became this detailed photograph, which I obtained through the department of mapping and land use. You can get such photographs of the whole country by choosing, off a map, which you want. I chose a number that had personal significance in some way, but where I myself would not go. In South Africa, particularly in that era, space and place were deeply politicised — they have very powerful social and personal implications.

Installation view of Miradas Borrosas at Gallus Zentrum, Frankfurt/Main, GER, 2019

SC: In your book, David Bunn writes about how satellite imagery can miss or obscure the texture of everyday life, erasing signs of human presence or occupation. It’s the kind of thing that Staples’ music video undoes, where you see people occupying space very intentionally. It’s closer to home, but at the same time, you don’t always have that level of control. Interventions like that of Mathias and Anna make this quite apparent. It also reminds me of your work Ashburton, and how you superimpose yourself onto the landscape.

JW: Yeah. We were talking about photography’s relation to surveillance and control, but it can also be a positive thing, about marking where and what things are, for all sorts of purposes. In a negative way, it’s about effecting what happens in that space, from a distance — to not actually engage with the lived reality of that space. You see everything from really far, from your airplane or on your computer screen. . . I suppose Ashburton came from thinking about what it means to be located in a place. There is this emotional connection, but in South Africa there is this powerful political structure of inclusion and exclusion, which was literally mapped out — who was allowed to be where and what this meant; what it meant for me, and my parents to own a great big farm, you know? Where did they get that farm? How did they get to be there? What were the implications? And how does that position me, as someone who is located by my whiteness? Those questions have a set of political, cultural, and personal positionings which are both enabling and disabling in all sorts of complicated ways. Over the years I’ve become more conscious of trying to make sense of that, for my own sense of who I am, how I am in the world, and why. All my work is roughly infused with those early experiences. One is located in all sorts of places with all sorts of histories. My father came from Ireland. He ended up in South Africa because he married my mother. It’s a very personal thing, but it has implications in the context of South Africa.

Mapping is a relatively objective thing. You mark out, measure, indicate what is supposedly there. But the other side of that mapping is personal — how do you layer yourself onto that? That’s why I really like that relationship between GSV and that narrative of the man driving around in his car telling the story of those people. It’s a beautiful thing! It speaks about the intersection of that objectivity and the real, lived experiences of people.

MW: With Ashburton, as with much of your other work, there is this index or meta data that seems to run parallel to the GSV click that you do to go to the next image, which is taken like a hundred metres further along the road. You may see the same person in both images, knowing that something happened in between, because it’s not the same moment. If you search on GSV, you will find that things are happening. We recently came across a little boy in Krugersdorp who is pictured taking off his shoes. He then walks on his socks through a small community. You ask yourself, why did he take off his shoes? Then you take these images, as printouts, to the site and you ask people, ‘Here is someone standing in front of this house. Do they still live here?’ The people currently living in the house say, ‘No. The family moved because this person, the father, passed away.’ So there are these deep, emotional moments; losing someone who is very important to you, only to find them appear on GSV. This can have deep implications.

Installation view of Blurry Gazes at Synnika, Frankfurt/Main, GER, 2023

JW: I made Ashburton in 1977. I had a map of the area, and marked out six or nine points that were equidistant, in a pseudo-scientific way. The actual experience of doing it, however, was quite different. My wife was taking the photographs of me standing in the field. I would tramp through the long grass, climb the fence, and walk down through some bushes and stand, and she would say, ‘No, go to the side,’ or, ‘Go to the middle.’ It’s a much more interesting set of actions. That’s the picture, done. You walk back to the road and on to the next site. That work doesn’t have all of these intervening, real life experiences. It’s just one pic that represents that particular moment.

SC: I wanted to ask about the tendency to catalogue and index in your respective practices, and how setting up such limits or structures in which to work relates to this personal component?

JW: It’s difficult to unravel. Is this some sort of psychological need for clarity? I don’t know. But artists are also subject to the language of art-making at a particular time. As a student, I was interested in the kind of work done by land artists in America. Or people like Bernd and Hilla Becher — German artists who were photographing industrial structures in a systematic way. Their approach resonated with me. It opened up new possibilities for working. I guess there’s also some autobiographical aspect; little resonances to things that were meaningful. When I was a teenager, for example, I spent my school holidays helping my father establish the farm. We spent days marking out tree orchards with a surveying beacon, measuring and pacing fields. When I became a student, we were asked to make a landscape drawing. I thought, well, my interest in landscape goes back a few years to when I literally entered the landscape and was walking across these fields. Photography became a useful way to mark and document that. When you’re doing something site-specific, walking across the field, you also start to think, ‘Well, I’ll have to photograph this so that there’s some kind of record that this thing has been done.’ I was interested in the photograph purely as a record.

Subsequent work used that mode a lot too. I was interested in marking and mapping the Tropic of Capricorn across the southern part of the world. When I was in Australia, I went to the middle of the country to find a section of the Tropic, using my GPS. I then walked for a few hundred metres along the line, photographing every metre. It’s a very long work, just photographing a piece of ground along a geographical point. I did the same in São Paulo. Some friends and I found a street which the Tropic ran down the middle of. I was interested in that because it was really the notion of what the south means, you know? The south is determined by the Tropic of Capricorn. There’s a whole series of works like that, where you set something up to feel like the system is producing the work. There’s also a work with termite mounds. I drove around and found a field that was speckled with termite mounds. I marked out 100 x 100 metres square, and photographed every single termite mound within that, like a scientist would. That led to another wor,k which was just a very long number of photographs of termite mounds. It resonates with processes that are used in scientific ways, like when an archeologist marks out a piece of ground and then marks everything within it. It’s a way of setting up a system.

Public intervention Status Quo Ladder, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

SC: Mathias you also mention the serial nature of Status Quo Ladder (2018–ongoing) as having personal significance, in that it ‘marks’ different stations in your life.

MW: Like Jeremy’s work, Status Quo Ladder is also a document of my presence in a particular place — that’s how interventions work. It’s an index of site, a sign that says, ‘I was here!’ Status Quo Ladder revolves around this ladder in Jerusalem, which leans on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where they say Jesus is buried. It’s a very holy place in Christianity, but there’s this ladder that stands on a pedestal on the facade. It’s not functional or useful, but every tourguide in the city will tell you anecdotes about it, and how, for hundreds of years, nobody has been allowed to move it. That’s the ‘status quo’: an agreement by all the Christian communities that there must be consensus from everyone to enact any change, architectural or otherwise. As with most things, there is never any consensus, so the ladder continues to lean on the facade, where it was placed hundreds of years ago. There are very old woodcuts, paintings, and more recently, photographs of the church which show this ladder. Most would agree that the ladder is totally profane, but I wanted to extend and multiply this strange occurence, to make it a ritual, by taking the idea to different places that I visit, installing ladders, and calling them ‘Status Quo Ladders.’ I started doing this in 2018, and recently installed a ladder here at NIROX.

SC: You’ve also spoken about how ubiquitous ladders are. You find them in public spaces all the time, throughout the world, but they also have they’re also loaded objects, historically and theologically. You said you’re more interested in it as a tool than as, say, a stairway to heaven, and how, for you, the ladder is like a bridge or stepping stone. It’s about accessibility, which you also speak about in relation to Indices (2021), where the fence is cut, enabling the transgression of a boundary. Jeremy, you mentioned this when talking about the aerial photographs, but you see it in other works too, like Xoe (2000). . .

JW: Fences are powerful things. My first time working with a fence came from looking at a map. I was invited to make a site-specific work in Nieu-Bethesda, in the Karoo. In preparation, I got a map of the area, and it was essentially an indication of divisions: farm divisions, property ownership. You’re immediately faced with this thing about the land; an open space that has been organised and structured through a series of separations. The original inhabitants of that land had a very different sense of what it meant to live on the land. I’m simplifying enormously, but for the early communities who occupied these spaces, land was something that you moved across. It wasn’t about ownership. That came with the coloniser: the soldier, closely followed by the surveyor. This is the colonial project: it’s about the ownership of land. So fencing, for me, is a very simple but powerful thing. A fence goes from one side to another, but it also prevents people from doing this. When you climb through the fence you’re doing something that is potentially illegal. Of course, if it’s your own fence, you’re just climbing through it, but if it’s not — if you’re a trespasser — that has powerful implications. They connect and disconnect, include and exclude. I’ve made a number of works on fences; marking the fence, drawing attention to it. In Australia, Jonathan Anthony Rose made a work by playing his violin bow on the fence. It’s a beautiful piece of music, actually.

Installation view of Indices at HfG Offenbach, Offenbach/Main, GER, 2020

MW: Over the last few weeks we’ve seen how prominent fences are here in South Africa. This palisade fencing seems to be everywhere. Because GSV merge different photographs from different angles, over 360 degrees, the repetition found in such fences cause glitches in the algorithm. Sometimes, in the poorer areas, you click on an image and you think you’ve found a glitch in a fence, but when you look closer you realise that it’s not; that the ‘glitch’ has been made by people improvising when building the fence around their property.

SC: You can also see through a fence, as opposed to a wall, which is opaque. With the GSV footage, Anna and Mathias mention the contrast between an area like Nietgedacht, where you’re able to see right into someone’s front yard, versus Roodeport, where it’s all high walls. Jeremy it also reminded me a bit of Veranda (2006) and this idea of labour, because in the wealthier areas like Roodeport, you see people in the process of labour, as opposed to relaxing on the stoep.

JW: With that work, I was thinking about my childhood home, which had a large veranda out front, this red stoep. We spent a lot of time on the veranda. We had our meals there, drinks in the evening, all those kinds of things. I think back, as an older person, to what it was like as a child, and how that space was managed by household servants. They would be up in the morning, on their hands and knees, polishing with a brush so that when we all came out in the morning it was nice and shiny, you know? As a child I was unaware of what that meant. As an older person, it is such a troubling memory. Who was this person? I knew her name, but I didn’t know much more than that. She was just a person there, doing work. That was part of this very difficult, deeply racialised, deeply gendered context in which I was implicated. And your implication is something that you just leave there, as a thing. Now, what do I then do with this troubling feeling? For this work, I wanted to reconstitute something of that. It was created on the floor of the parking lot. Colleen and I marked out the 1:1 scale and shape of my childhood verandah, and got on our hands and knees and polished the parking lot floor until it was reasonably shiny. It was nothing like the everyday labour that our household servants did, it’s not a recompense for that problematic history, but there was some indicationof it. I suppose it’s also a mapping back through time, thinking about this space. But a verandah is also a transitional space between insideand outside, which I like.

MW: On GSV, you can often see between the street and the house. In smaller communities, this transitional space is usually bigger than the house itself. But in rich neighbourhoods, you don’t really see this space. If you do, you mostly see workers: gardeners or those who work around the house but don’t live in it.

AB: We realised quite early on in our residency that the places around here are very different. The places with huge fences and walls are less accessible for us.

MW: Yes, especially these gated communities. You reach a gate and can’t go inside unless you’re a part of the community or are invited. Other places don’t seem accessible because we don’t know what it will be like for us as foreigners to go there. This is something that we need to face, and it’s a big part of our project — which parts of the map can we access and which parts can’t we? The fences are a visible layer of this protective element. Of course, we want to be safe when on foot in these communities, but the last thing we want to do is offend someone in their private space. As artists we need to be very conscious of this. And of course, this is also the controversy around GSV.

Installation view of PF012303 at NIROX Scupture Park, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

JW: Yes, going into spaces is never a neutral activity. Who you are, who the people are who live there. . . It’s charged. In South Africa, where the divisions between people who have and people who don’t are so evident, the freedom that an artist might experience to just go there and do stuff and take photographs exposes more complex social relationships. I’m so conscious of that here in Paris. I can walk everywhere, go everywhere. In other cities, like Johannesburg, it can be quite a complex and problematic relationship. It needs to be negotiated in some way.

SC: Mathias, you mentioned gated communities as these black holes on GSV. Such communities usually have a lot of security: cameras around and so on, that view everything happening on its periphery. Someone sits in a security office somewhere watching all of this. It’s like a panopticon. GSV could be said to perform a similar function. There are people in the communities that you’ve been into who haven’t seen these images, or haven’t had access to them, but their world is visible. The world that’s financially protected is not. There’s something about this complication, that Jeremy is talking about, where you physically go into a space, where you have to interact with people, as opposed to doing so online, from the comfort of your living room.

JW: It’s perhaps more apparent in a place like Johannesburg. I’m told that London is the most surveilled public space imaginable. Every street is under the camera gazes. These complex systems are designed to trigger a response if something untoward happens. This is the post-9/11 world, one that is hyper-conscious of the so-called threat of terrorism. Someone sleeping on a park bench is being monitoredand someone somewhere is watching. The next thing a police car draws up and gets them to move on. So while cities like London or Paris appear to be open, free, they’re also deeply controlled. It may not be so apparent when walking down the street, but you’re being watched. That sounds like an exaggeration, but in many ways it’s true, particularly for those who might be regarded as dangerous, however that’s defined.

SC: At this point, I’d like to open the conversation up to the audience, and begin by reading one of the questions that’s been asked in the chat, which is directed to you, Jeremy: ‘How has your reading of your work changed over time, and please could you speak through this? Does the meaning change? Also in relation to personal and sociopolitical life events?’

Video still of Blurry Gazes, Nietgedacht, ZAF, 2023

JW: It’s difficult to answer that. I’ve been working for a long time. When I look back at works that I made in the 70s or 80s, I inevitably see them through the lens of my present situation; I can’t entirely reconstruct what it was like to be a twenty-five year old artist and what I was thinking about — you’re negotiating the situation that you’re in. I suppose, in some ways, all of the work that I’ve done accumulates a sort of backstory, which inevitably reflects forward onto the work I’m making now. I’m still interesting in the same subjects. I’m still interested, say, in fences, so when I see a work with a fence now I cannot but think about earlier works I made with fences. It loops, backwards and forwards. I suppose you also develop ways of working. I’m in Paris now, so inevitably I think, ‘Ok, I’m going to map a walk across Paris. I’m going to start in the north and walk down to the south, and systematically mark the journey through those spaces.’ Why? Because there are ways in which you work, and you presumably develop a more nuanced sense about what those things might mean. The 70s and 80s in South Africa were the most extreme time of the political struggle, and one was involved in that, in whichever way. It inevitably coloured what you were doing. If you made a work then about climbing through a fence it had to be understood, or could not but be understood, in terms of who is and is not allowed to climb through a fence. If you make it now, it’s somewhat different, but only just.

MW: Sven and I had a conversation yesterday about the privilege of artists; the privilege of being able to climb a fence and go somewhere, to break into some system and engage, because of how artists are perceived, at least in Germany. You have this excuse.

Audience: Who is watchable? A few years ago, I went onto Google and looked for Osama Bin Laden’s residence. I was able to locate it, and to basically zoom into his residence. That meant he was watchable. I somehow doubt we could do that with the president’s residence in the United States. You wouldn’t get anywhere close to the White House. Looking at the footage, it’s so much easier to access people in the lower rungs of society, as opposed to someone in Sandton, behind those high walls. There are 24,000 plus satellites circling earth, so everybody is watchable, but some people are obviously more watchable than others.

MW: Earlier this year I was doing a project about the German Autobahn. I wanted to work with content created by some webcams, that film the Autobahn all day long. While working, every single webcam on the Autobahn turned off. This was at the time when Russia started invading Ukraine. I asked the service if this was related and they didn’t give me a precise answer, but I’m pretty sure they were, because when you were physically on the Autobahn you could see military transport.

SC: For me, this is where the glitch or infringement becomes really interesting. . . The interruption of that regularity exposes a whole bunch of things.

Installation view of Autobahn Aktion at Kunstverein Bellevue Saal, Wiesbaden, GER, 2022

Published in FORM Journal, Sven Christian (Ed.), published by Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture, 2023

Owners, Guests, and Trespassers

Sven Christian in conversation with Jeremy Wafer, Anna Boldt, and Mathias Weinfurter, 2023

On Thursday, 15 December, the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture and NIROX hosted a webinar with Jeremy Wafer, Anna Boldt, and Mathias Weinfurter, moderated by Sven Christian. The webinar took place in the early stages of Boldt and Weinfurter’s residency at NIROX, and served as an introduction to Wafer’s work, who took up residence a few months later, on 16 May 2023, in preperation for an exhibition at Goodman Gallery that opens on 9 July 2023.

The webinar focused on land, mapping, surveillance, and the potential failures of photographic representation. It included the screening of a short film by Boldt and Weinfurter, titled Miradas Borrosas (Blurry Gazes), which revolves around the presence of Google Street View (GSV) in the small Colombian village of Ambalema, before delving into their current research on GSV in Nietgedacht, 40km from Johannesburg, as well as Wafer’s own photographic, sculptural, and sitespecific interventions, such as Ashburton (1977), Fence (1979), and Xoe (2000).

The conversation was subsequently transcribed by Zanele Mashinini and included here to provide some background information about the works produced during their respective residencies.

Installation view of Palisade Fences at NIROX Sculpture Park, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

Sven Christian: Jeremy, let’s start by talking about the show that you’re preparing for, at Goodman Gallery?

Jeremy Wafer: The show is a continuation of works that I’ve been doing. I did a small show at Goodman Gallery in London in February / March that included older works — that curvy wax piece and some smaller ones that combine mapping and marking. There was a little stripey work, and I’m currently working on a whole series of drawings, taking pages from a financial newspaper andgoing through a series of permutations of single and broken lines. There will be about sixty of these drawings. It’s the sort of thing that I can do while I’m here in Paris. I have a room studio, so I can’t really make the sculptural works here. At the moment it’s quite a rhythmical exercise. Then I’m expecting to work on a series of maps. I’ve got a series of 1:50,000 maps arriving from Johannesburg, with all sorts of South African locations. I really love their quality, as physical objects. It’s interesting to go to different countries and look for the standard government maps. They have a very different physical format. The South African ones are particularly nice. They‘re printed on strong paper, in portrait format, and are beautifully produced. I have access to a pile of those, and I’m going to interfere with the map — blocking out areas, treating them as signs or fields. . . Sometimes painting out the actual map, leaving out all the descriptive stuff around the edge. That’s one set of work, but I’m also anticipating about eight sculptural pieces of different sizes.

I’m getting to a stage where I just want to work on a fairly simple, direct idea. I suppose the running thread through a lot of the work is an interest in the materiality of ordinary stuff — tar, soap, stuff like that, which is quite low budget. In recent years my exhibitions have included a mixture of things that are not directly connected, but when there are a whole lot of works together, say six or seven, they establish an open kind of relationship.

SC: The ones from the Financial Times look like they’re redacted.

JW: Because it’s newspaper, I suppose those marks take on that quality, particularly in light of South African history. It’s not something I want to make too much of, but a lot of these works also resonate with personal experience. A long time ago, when I was in the army, I was a clerk, and had to block out things that were in soldiers’ letters; I had to read the letters and take a black pen and remove anything that might relate to a mission: like if a soldier wrote and said, ‘Oh, we were at X, Y, or Z in Namibia.’ You weren’t allowed to say that. There was this thing about location and blocking, but I don’t think these works stem from that. When you work with things, you start to see connections to a host of other experiences or to things that you have done or have had some relationship to.

Video still of Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

SC: Reading those letters must have been a strangely intimate experience. There’s this inadvertent voyeuristic element that overlaps with the research that Mathias and Anna are doing on Google Street View [GSV], which began in Colombia. Perhaps you could give some background context to it, your research, and the project that came about as a result?

Mathias Weinfurter: Sure. Miradas Borrosas was realised by Anna and I during a residency in February 2019 in the small village of Ambalema, five hours west of Bogota. To prepare, we wanted to get a better sense of the village, so we went onto GSV, where we were able to ‘walk’ through, while sitting in Germany. The GSV content for this village was produced in July 2013, so at the time of our project it was already six years old. The images captured a number of people standing outside their homes, in front of shops, in the park. . . You saw a lot of people, with their faces blurred. Some look straight into the camera.

Anna Boldt: When we arrived there, we noticed that very little had changed. The streets and buildings look almost the same. A lot of the same people featured on GSV were also often in the same place. We began to converse with them, and found that they didn’t know about GSV; that they don’t use this service. We had brought printouts of the images with us, and they were surprised by them. It turns out that, in a place like Ambalema, which is really small, it was easy to find these people because everyone knows each other. Although their faces were blurred, they were still recognisable. We wanted to know if they could remember the day when these pictures were taken, and it was fascinating to hear their stories. There was a lot of speculation about the car, in particular, because it’s a very weird looking car with this camera on top. In the context of Colombia, many people thought it was related to the drug war; these paramilitary groups that were entering such villages at the time, or that this vehicle was somehow connected to the police.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

MW: We were so inspired by these conversations about the day that the car passed through the village that we wrote a story, which you hear in the film. We then collaborated with Alfredo Martínez, who has this megaphone equipped to his car. It’s quite commonplace in these small Colombian villages. Everyday Alfredo drives around, speaking into the megaphone, to tell the news. You can pay him to spread news about, say, the opening of a new restaurant. So together with him we realised a performance, in which he drove around reading the story that we wrote about the day when GSV passed through Ambalema. In the story, we tried to include a number of the speculations that we’d heard.

Our second intervention was trying to reinterpret the images from GSV, in cooperation with the inhabitants. We built a wooden tower that echoed the perspective of that on the GSV car. We went through the town with this tower, trying to recapture images of the same places, from the same perspective. A lot of the time we found the same protagonists there, as before. The documentation of both interventions is reflected in the film.

Of course, we also did further research, and found some historical references that were quite inspiring. The first was a film, The man with a movie camera, that was produced by Dziga Vertov in 1929, in Ukraine. A lot of the scenes are filmed from a car with a camera on top. The film is about him going around filming himself, so there’s footage from the car but also of him doing this intervention. Then we found an interesting example from the 60s, of Josep Planas i Montanyà. He was a photographer, living and working on the isle of Mallorca. He ran a business producing postcards, and would go around in his car, which also had a camera on top, to document the streets and island.

GSV was launched, almost worldwide, in 2008. It led to some artistic projects, such as Vince Staples’ music video, FUN! (2018), by director Calmatic. The video combines the aesthetics and mechanisms of GSV with the codes of hip-hop and pop culture.

Public intervention Miradas Borrosas, Ambalema, COL, 2019

SC: That video begins with a distant view of the Earth, then zooms into a particular community, a particular suburb, and the different inhabitants going about their day. There’s a voyeuristic element to it, but what struck me is how the director flips this — it becomes a way of putting one’s community on the map and reflects a kind of agency or reclaiming of that digital space. Jeremy, I know that as a student you also started documenting the various houses in the street in which you lived. . .

JW: Ja. I suppose I came to photography as a very direct form of documentation. It was systematic for me, like mapping. My early student work was just photographing all the houses in my street. I would start at one end and go all the way down. When you start doing that, you’re not making any aesthetic choices. You have a system in place which you work through. In the process, one has other sorts of interactions. People came out of their homes to ask if I was an estate agent. That sort of thing wasn’t part of the work, but I suppose it’s one of the reasons why I was interested in your film, because you see the relationship between the systematic, objective component of GSV, going up an down the street, but you also layer that with a more personal, human narrative. It’s a poetic and imaginative kind of layering.

I began thinking about mapping space before GSV or Google Earth existed; accessing aerial photographs of sites which I myself would not go to. In the context of South Africa, which is such a demarcated country, the separation and division that one experiences is not only of people but of space. There were places that one could or could not visit, and I became interested in how such images might provide a form of access, through this dislocated eye — how you could see something without physically going there. There’s this imaginative transfer. For example, there is an aerial photograph of an area near where I grew up. During apartheid it was demarcated as a ‘native reserve’; an area for black people. Now, I could see this area from the veranda of my parents’ farm, in the white area. We could look up into the hills and see it, but we never went there. It was a place which wasn’t ‘for us’; a place which was ‘other.’ My only access became this detailed photograph, which I obtained through the department of mapping and land use. You can get such photographs of the whole country by choosing, off a map, which you want. I chose a number that had personal significance in some way, but where I myself would not go. In South Africa, particularly in that era, space and place were deeply politicised — they have very powerful social and personal implications.

Installation view of Miradas Borrosas at Gallus Zentrum, Frankfurt/Main, GER, 2019

SC: In your book, David Bunn writes about how satellite imagery can miss or obscure the texture of everyday life, erasing signs of human presence or occupation. It’s the kind of thing that Staples’ music video undoes, where you see people occupying space very intentionally. It’s closer to home, but at the same time, you don’t always have that level of control. Interventions like that of Mathias and Anna make this quite apparent. It also reminds me of your work Ashburton, and how you superimpose yourself onto the landscape.

JW: Yeah. We were talking about photography’s relation to surveillance and control, but it can also be a positive thing, about marking where and what things are, for all sorts of purposes. In a negative way, it’s about effecting what happens in that space, from a distance — to not actually engage with the lived reality of that space. You see everything from really far, from your airplane or on your computer screen. . . I suppose Ashburton came from thinking about what it means to be located in a place. There is this emotional connection, but in South Africa there is this powerful political structure of inclusion and exclusion, which was literally mapped out — who was allowed to be where and what this meant; what it meant for me, and my parents to own a great big farm, you know? Where did they get that farm? How did they get to be there? What were the implications? And how does that position me, as someone who is located by my whiteness? Those questions have a set of political, cultural, and personal positionings which are both enabling and disabling in all sorts of complicated ways. Over the years I’ve become more conscious of trying to make sense of that, for my own sense of who I am, how I am in the world, and why. All my work is roughly infused with those early experiences. One is located in all sorts of places with all sorts of histories. My father came from Ireland. He ended up in South Africa because he married my mother. It’s a very personal thing, but it has implications in the context of South Africa.

Mapping is a relatively objective thing. You mark out, measure, indicate what is supposedly there. But the other side of that mapping is personal — how do you layer yourself onto that? That’s why I really like that relationship between GSV and that narrative of the man driving around in his car telling the story of those people. It’s a beautiful thing! It speaks about the intersection of that objectivity and the real, lived experiences of people.

MW: With Ashburton, as with much of your other work, there is this index or meta data that seems to run parallel to the GSV click that you do to go to the next image, which is taken like a hundred metres further along the road. You may see the same person in both images, knowing that something happened in between, because it’s not the same moment. If you search on GSV, you will find that things are happening. We recently came across a little boy in Krugersdorp who is pictured taking off his shoes. He then walks on his socks through a small community. You ask yourself, why did he take off his shoes? Then you take these images, as printouts, to the site and you ask people, ‘Here is someone standing in front of this house. Do they still live here?’ The people currently living in the house say, ‘No. The family moved because this person, the father, passed away.’ So there are these deep, emotional moments; losing someone who is very important to you, only to find them appear on GSV. This can have deep implications.

Installation view of Blurry Gazes at Synnika, Frankfurt/Main, GER, 2023

JW: I made Ashburton in 1977. I had a map of the area, and marked out six or nine points that were equidistant, in a pseudo-scientific way. The actual experience of doing it, however, was quite different. My wife was taking the photographs of me standing in the field. I would tramp through the long grass, climb the fence, and walk down through some bushes and stand, and she would say, ‘No, go to the side,’ or, ‘Go to the middle.’ It’s a much more interesting set of actions. That’s the picture, done. You walk back to the road and on to the next site. That work doesn’t have all of these intervening, real life experiences. It’s just one pic that represents that particular moment.

SC: I wanted to ask about the tendency to catalogue and index in your respective practices, and how setting up such limits or structures in which to work relates to this personal component?

JW: It’s difficult to unravel. Is this some sort of psychological need for clarity? I don’t know. But artists are also subject to the language of art-making at a particular time. As a student, I was interested in the kind of work done by land artists in America. Or people like Bernd and Hilla Becher — German artists who were photographing industrial structures in a systematic way. Their approach resonated with me. It opened up new possibilities for working. I guess there’s also some autobiographical aspect; little resonances to things that were meaningful. When I was a teenager, for example, I spent my school holidays helping my father establish the farm. We spent days marking out tree orchards with a surveying beacon, measuring and pacing fields. When I became a student, we were asked to make a landscape drawing. I thought, well, my interest in landscape goes back a few years to when I literally entered the landscape and was walking across these fields. Photography became a useful way to mark and document that. When you’re doing something site-specific, walking across the field, you also start to think, ‘Well, I’ll have to photograph this so that there’s some kind of record that this thing has been done.’ I was interested in the photograph purely as a record.

Subsequent work used that mode a lot too. I was interested in marking and mapping the Tropic of Capricorn across the southern part of the world. When I was in Australia, I went to the middle of the country to find a section of the Tropic, using my GPS. I then walked for a few hundred metres along the line, photographing every metre. It’s a very long work, just photographing a piece of ground along a geographical point. I did the same in São Paulo. Some friends and I found a street which the Tropic ran down the middle of. I was interested in that because it was really the notion of what the south means, you know? The south is determined by the Tropic of Capricorn. There’s a whole series of works like that, where you set something up to feel like the system is producing the work. There’s also a work with termite mounds. I drove around and found a field that was speckled with termite mounds. I marked out 100 x 100 metres square, and photographed every single termite mound within that, like a scientist would. That led to another wor,k which was just a very long number of photographs of termite mounds. It resonates with processes that are used in scientific ways, like when an archeologist marks out a piece of ground and then marks everything within it. It’s a way of setting up a system.

Public intervention Status Quo Ladder, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

SC: Mathias you also mention the serial nature of Status Quo Ladder (2018–ongoing) as having personal significance, in that it ‘marks’ different stations in your life.

MW: Like Jeremy’s work, Status Quo Ladder is also a document of my presence in a particular place — that’s how interventions work. It’s an index of site, a sign that says, ‘I was here!’ Status Quo Ladder revolves around this ladder in Jerusalem, which leans on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where they say Jesus is buried. It’s a very holy place in Christianity, but there’s this ladder that stands on a pedestal on the facade. It’s not functional or useful, but every tourguide in the city will tell you anecdotes about it, and how, for hundreds of years, nobody has been allowed to move it. That’s the ‘status quo’: an agreement by all the Christian communities that there must be consensus from everyone to enact any change, architectural or otherwise. As with most things, there is never any consensus, so the ladder continues to lean on the facade, where it was placed hundreds of years ago. There are very old woodcuts, paintings, and more recently, photographs of the church which show this ladder. Most would agree that the ladder is totally profane, but I wanted to extend and multiply this strange occurence, to make it a ritual, by taking the idea to different places that I visit, installing ladders, and calling them ‘Status Quo Ladders.’ I started doing this in 2018, and recently installed a ladder here at NIROX.

SC: You’ve also spoken about how ubiquitous ladders are. You find them in public spaces all the time, throughout the world, but they also have they’re also loaded objects, historically and theologically. You said you’re more interested in it as a tool than as, say, a stairway to heaven, and how, for you, the ladder is like a bridge or stepping stone. It’s about accessibility, which you also speak about in relation to Indices (2021), where the fence is cut, enabling the transgression of a boundary. Jeremy, you mentioned this when talking about the aerial photographs, but you see it in other works too, like Xoe (2000). . .

JW: Fences are powerful things. My first time working with a fence came from looking at a map. I was invited to make a site-specific work in Nieu-Bethesda, in the Karoo. In preparation, I got a map of the area, and it was essentially an indication of divisions: farm divisions, property ownership. You’re immediately faced with this thing about the land; an open space that has been organised and structured through a series of separations. The original inhabitants of that land had a very different sense of what it meant to live on the land. I’m simplifying enormously, but for the early communities who occupied these spaces, land was something that you moved across. It wasn’t about ownership. That came with the coloniser: the soldier, closely followed by the surveyor. This is the colonial project: it’s about the ownership of land. So fencing, for me, is a very simple but powerful thing. A fence goes from one side to another, but it also prevents people from doing this. When you climb through the fence you’re doing something that is potentially illegal. Of course, if it’s your own fence, you’re just climbing through it, but if it’s not — if you’re a trespasser — that has powerful implications. They connect and disconnect, include and exclude. I’ve made a number of works on fences; marking the fence, drawing attention to it. In Australia, Jonathan Anthony Rose made a work by playing his violin bow on the fence. It’s a beautiful piece of music, actually.

Installation view of Indices at HfG Offenbach, Offenbach/Main, GER, 2020

MW: Over the last few weeks we’ve seen how prominent fences are here in South Africa. This palisade fencing seems to be everywhere. Because GSV merge different photographs from different angles, over 360 degrees, the repetition found in such fences cause glitches in the algorithm. Sometimes, in the poorer areas, you click on an image and you think you’ve found a glitch in a fence, but when you look closer you realise that it’s not; that the ‘glitch’ has been made by people improvising when building the fence around their property.

SC: You can also see through a fence, as opposed to a wall, which is opaque. With the GSV footage, Anna and Mathias mention the contrast between an area like Nietgedacht, where you’re able to see right into someone’s front yard, versus Roodeport, where it’s all high walls. Jeremy it also reminded me a bit of Veranda (2006) and this idea of labour, because in the wealthier areas like Roodeport, you see people in the process of labour, as opposed to relaxing on the stoep.

JW: With that work, I was thinking about my childhood home, which had a large veranda out front, this red stoep. We spent a lot of time on the veranda. We had our meals there, drinks in the evening, all those kinds of things. I think back, as an older person, to what it was like as a child, and how that space was managed by household servants. They would be up in the morning, on their hands and knees, polishing with a brush so that when we all came out in the morning it was nice and shiny, you know? As a child I was unaware of what that meant. As an older person, it is such a troubling memory. Who was this person? I knew her name, but I didn’t know much more than that. She was just a person there, doing work. That was part of this very difficult, deeply racialised, deeply gendered context in which I was implicated. And your implication is something that you just leave there, as a thing. Now, what do I then do with this troubling feeling? For this work, I wanted to reconstitute something of that. It was created on the floor of the parking lot. Colleen and I marked out the 1:1 scale and shape of my childhood verandah, and got on our hands and knees and polished the parking lot floor until it was reasonably shiny. It was nothing like the everyday labour that our household servants did, it’s not a recompense for that problematic history, but there was some indicationof it. I suppose it’s also a mapping back through time, thinking about this space. But a verandah is also a transitional space between insideand outside, which I like.

MW: On GSV, you can often see between the street and the house. In smaller communities, this transitional space is usually bigger than the house itself. But in rich neighbourhoods, you don’t really see this space. If you do, you mostly see workers: gardeners or those who work around the house but don’t live in it.

AB: We realised quite early on in our residency that the places around here are very different. The places with huge fences and walls are less accessible for us.

MW: Yes, especially these gated communities. You reach a gate and can’t go inside unless you’re a part of the community or are invited. Other places don’t seem accessible because we don’t know what it will be like for us as foreigners to go there. This is something that we need to face, and it’s a big part of our project — which parts of the map can we access and which parts can’t we? The fences are a visible layer of this protective element. Of course, we want to be safe when on foot in these communities, but the last thing we want to do is offend someone in their private space. As artists we need to be very conscious of this. And of course, this is also the controversy around GSV.

Installation view of PF012303 at NIROX Scupture Park, Krugersdorp, ZAF, 2023

JW: Yes, going into spaces is never a neutral activity. Who you are, who the people are who live there. . . It’s charged. In South Africa, where the divisions between people who have and people who don’t are so evident, the freedom that an artist might experience to just go there and do stuff and take photographs exposes more complex social relationships. I’m so conscious of that here in Paris. I can walk everywhere, go everywhere. In other cities, like Johannesburg, it can be quite a complex and problematic relationship. It needs to be negotiated in some way.

SC: Mathias, you mentioned gated communities as these black holes on GSV. Such communities usually have a lot of security: cameras around and so on, that view everything happening on its periphery. Someone sits in a security office somewhere watching all of this. It’s like a panopticon. GSV could be said to perform a similar function. There are people in the communities that you’ve been into who haven’t seen these images, or haven’t had access to them, but their world is visible. The world that’s financially protected is not. There’s something about this complication, that Jeremy is talking about, where you physically go into a space, where you have to interact with people, as opposed to doing so online, from the comfort of your living room.

JW: It’s perhaps more apparent in a place like Johannesburg. I’m told that London is the most surveilled public space imaginable. Every street is under the camera gazes. These complex systems are designed to trigger a response if something untoward happens. This is the post-9/11 world, one that is hyper-conscious of the so-called threat of terrorism. Someone sleeping on a park bench is being monitoredand someone somewhere is watching. The next thing a police car draws up and gets them to move on. So while cities like London or Paris appear to be open, free, they’re also deeply controlled. It may not be so apparent when walking down the street, but you’re being watched. That sounds like an exaggeration, but in many ways it’s true, particularly for those who might be regarded as dangerous, however that’s defined.

SC: At this point, I’d like to open the conversation up to the audience, and begin by reading one of the questions that’s been asked in the chat, which is directed to you, Jeremy: ‘How has your reading of your work changed over time, and please could you speak through this? Does the meaning change? Also in relation to personal and sociopolitical life events?’

Video still of Blurry Gazes, Nietgedacht, ZAF, 2023

JW: It’s difficult to answer that. I’ve been working for a long time. When I look back at works that I made in the 70s or 80s, I inevitably see them through the lens of my present situation; I can’t entirely reconstruct what it was like to be a twenty-five year old artist and what I was thinking about — you’re negotiating the situation that you’re in. I suppose, in some ways, all of the work that I’ve done accumulates a sort of backstory, which inevitably reflects forward onto the work I’m making now. I’m still interesting in the same subjects. I’m still interested, say, in fences, so when I see a work with a fence now I cannot but think about earlier works I made with fences. It loops, backwards and forwards. I suppose you also develop ways of working. I’m in Paris now, so inevitably I think, ‘Ok, I’m going to map a walk across Paris. I’m going to start in the north and walk down to the south, and systematically mark the journey through those spaces.’ Why? Because there are ways in which you work, and you presumably develop a more nuanced sense about what those things might mean. The 70s and 80s in South Africa were the most extreme time of the political struggle, and one was involved in that, in whichever way. It inevitably coloured what you were doing. If you made a work then about climbing through a fence it had to be understood, or could not but be understood, in terms of who is and is not allowed to climb through a fence. If you make it now, it’s somewhat different, but only just.

MW: Sven and I had a conversation yesterday about the privilege of artists; the privilege of being able to climb a fence and go somewhere, to break into some system and engage, because of how artists are perceived, at least in Germany. You have this excuse.

Audience: Who is watchable? A few years ago, I went onto Google and looked for Osama Bin Laden’s residence. I was able to locate it, and to basically zoom into his residence. That meant he was watchable. I somehow doubt we could do that with the president’s residence in the United States. You wouldn’t get anywhere close to the White House. Looking at the footage, it’s so much easier to access people in the lower rungs of society, as opposed to someone in Sandton, behind those high walls. There are 24,000 plus satellites circling earth, so everybody is watchable, but some people are obviously more watchable than others.

MW: Earlier this year I was doing a project about the German Autobahn. I wanted to work with content created by some webcams, that film the Autobahn all day long. While working, every single webcam on the Autobahn turned off. This was at the time when Russia started invading Ukraine. I asked the service if this was related and they didn’t give me a precise answer, but I’m pretty sure they were, because when you were physically on the Autobahn you could see military transport.

SC: For me, this is where the glitch or infringement becomes really interesting. . . The interruption of that regularity exposes a whole bunch of things.

Installation view of Autobahn Aktion at Kunstverein Bellevue Saal, Wiesbaden, GER, 2022

Published in FORM Journal, Sven Christian (Ed.), published by Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture, 2023